The phenomenon of female fandom, usually characterized by screaming, hysteria, mobs, excessive emotional investment, and other such pejorative descriptions, seems to have inspired rather charged responses, puzzlement and anxiety, since the beginning of cinema. It is within this context of excessive female fandom that early cinema star Rudolph Valentino, one of the first and therefore news-worthy figures to inspire such fervor in female fans, was and still is often discussed and remembered. When Valentino died in 1926, every major newspaper ran first-page coverage of the Latin Lover’s funeral, all headlining the mostly-female “throngs” of more than 30,000 who stopped traffic and caused riots, hurting more than 100 people and smashing two large windows in their frenzy to catch a last, short glimpse of the body of “Film’s Greatest Lover” (“Endless Throng”; “Thousands Riot”; “Valentino Passes”). These larger-than-life responses are just one anecdotal example of the many that make up the mythic legend that still persists as Rudolph’s Valentino’s star persona, the public image of the man who immigrated from Italy at eighteen and worked as a dancer before becoming one of early Hollywood’s biggest stars for masses of desiring female fans, idolized (by women) for the exotic sexuality that characterized his star vehicles and seemed also to exist in his “real life.”

Perhaps film historians felt the same discomfort over issues of feminine desire and fan excess which was evident in the sensationalized and somewhat condemnatory newspaper headlines of Valentino’s funeral and which was voiced by countless American men during the period of Valentino’s stardom, for the critical examination of stars and fans remained largely marginalized until the 1970s. Scholars like Richard Dyer, who produced some of the first scholarly work on stars, have been incredibly influential in the world of film studies and beyond, revealing the ways in which fans, stars, and the star system serve as sources of complex concepts and theories; they provide productive points of intervention for the investigation of Hollywood’s industrial and economic practices, its various constructions of desire, and the cultivation of consumerist spectators, especially in this historical moment of on-rushing modernity and a flourishing star system, as well as the complex processes of spectatorial engagement and identification, with both stars and film texts. Many feminist scholars of the 1970s and afterwards were deeply interested in female spectatorship and in reclaiming cinema and its histories for female practitioners and participants, and so, like Richard Dyer, have also taken up the study of fandom and stardom. Involved in both of these trends of scholarship are Miriam Hansen and Gaylyn Studlar, cultural film historians who each published responsive and overlapping yet differently-oriented work on Rudolph Valentino in the 1980s and 1990s, investigating his star image as part of their cultural reexamination of and intervention into (film) history.

One of the clearest sources of influence on both Hansen and Studlar, evident across their careers and particularly visible in their scholarship on Valentino, was the development of feminist film studies in the 1970s. According to film scholar and historian Patricia Erens, the development of feminist film studies was a product of Second-wave feminism, begun in the early 1960s, as well as of the inclusion of women’s studies in academia (xvi). Initially sociologically-focused, feminist film studies began by investigating the representations of female characters in filmic narratives and genres and the repercussions such popular representations had for social stereotypes of women. The movement then turned towards the semiotic, Marxist, and psychoanalytic (Freudian and then Lacanian and Althusserian) movements which were coming to dominate critical theories of the later 1970s. These feminist scholars thus became more centrally concerned with and examined film texts’ production of meaning, their positioning of the viewer, and the ways in which cinema’s very mechanisms affected the representation of women (xvii).

Considering such thematic and theoretical trends, the historical patterns evident in the bibliography of Valentino scholarship are themselves very interesting and point to the various ways in which the Valentino figure has been cast or been seen as useful or interesting in different cultural and critical moments. The 1970s witnessed not only the rise of feminism but also the publication of a plethora of biographies which focused on Valentino’s cult image and the sexualized, enigmatic legacy which persisted long after his untimely death in 1926 at the age of 31; examples include Norman Mackenzie’s The Magic of Valentino (1974) and Noel Botham and Peter Donnelley’s Valentino: The Love God (1976). Miriam Hansen and Gaylyn Studlar provide the only significant scholarship on Rudolph Valentino between these biographies of the 1970s and the 2000s, when a new wave of publications emerged. Returning after thirty years’ influence of feminist and gender studies, an increased interest in fandom, stardom, and spectatorship (additionally fueled by the recent explosion of internet- and reality TV-dominated celebrity culture), the upsurge in masculine studies since the 1990s, and the new vogue that silent cinema has been experiencing in the academy since the 1970s, these new biographies of the 2000s focused catalogue-like on “the first” male and female stars, looking to locate the film star and the phenomenon of fandom in early cinema history. Some of these more recent works, which also seem more interested in the dark side of Hollywood than in Valentino’s sexual allure, include Noel Botham’s Valentino: The First Superstar (2002), David Menefee’s collection of the First Male Stars (2007), Allen Ellenberger’s The Valentino Mystique: Death and Afterlife of the Silent Film Idol (2005) and Emily Leider’s Dark Lover (2003).

Responding to the influence of feminist, gender, and star studies and seeking to answer large-scale cultural and historical questions, Hansen and Studlar, unlike many of these (largely gossip-mongering) biographies and rather cursory star anthologies, forgo attempts to document the life and personality of Valentino himself; rather, these cultural film historians use the star figure of Rudolph Valentino to investigate the broader, contextualizing culture and history in which he became a star, which made him a star, which offered his star image to desiring spectators. They examine his constructed star image, the viewing strategies embedded in his films and their alignment of spectators and spectatorial identification, as well as the public reception (both male and female) of his star image during the 1920s. But beyond their shared cultural scope and their overlapping feminist and psychoanalytic interests and backgrounds, these two scholars have different questions and different goals in relation to cinema history, which directly shape their use of and research into Rudolph Valentino.

Miriam Hansen published her essay “Ambivalence, Pleasure, Identification: Valentino and Female Spectatorship” in 1986, initiating the new trend of critical Rudolph Valentino scholarship after the 1970s’ proliferation of biographies. Five years after this first essay, and after a published response from both Richard DeCordova and Gaylyn Studlar, Hansen published her book Babel and Babylon: Spectatorship in American Silent Film (1991); it expands upon the ideas begun in “Ambivalence” and represents a fuller rendering of her career-long investigation into (female) spectatorship and early cinema, especially as it pertains to the entirety of the cinematic experience and its relation to modernity, mass culture, and the public sphere.

As is clear from these broader research interests and her extensive resume of publications, Hansen is not only engaged with feminist studies but is also deeply influenced by the Frankfurt School, particularly Theodor Adorno, Walter Benjamin, and Siegfried Kracauer, who, drawing on Marxist theories, produced works discussing the frenetic, newly-arriving modernity of the 20th century and investigating entrenched dominant ideologies. The mass media of film was an important part of such study, seen as significant for the role it played in both the modern and ideological impacts on and interactions with the human sensorium at this time (and since then). In much of her professional bibliography, Hansen engages with these three Frankfurt theorists and both utilizes and advances their ideas of modernity and mass culture to investigate the entirety of the cinematic experience, particularly at the time of its introduction into and solidification within society in early 1900s. Hansen seeks to locate a/the historical space between American silent cinema and the so-called classical Hollywood cinema which dominated narrative filmmaking between the 1930s and the 1950s and whose legacy stretches through to today, registering the spectatorial and textual transitions that occurred in that shift towards the cementing of classical cinema and “the creation of this classical spectator,” especially in relation to this era’s transformation of the public sphere (Babel 16). Thus, as is so clearly evident in her psychoanalytic textual work on Valentino, Hansen is interested in the creation of spectatorship as we know it, in tracing, as Gaylyn Studlar so succinctly explains, “Hollywood’s creation of film-viewer relations during an era that solidified the cinema’s place in public life,” examining both textual and spectatorial transformations (“Response” 39).

In considering both Hansen’s and Studlar’s scholarship, it becomes important to acknowledge Laura Mulvey’s seminal, deeply-influential essay “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema” (1975), which was produced within the scope of influence of 1970s feminism as well as psychoanalytic- and Lacanian-influenced theories of film and feminism and considers the relation between gender and spectatorship; Hansen’s “Ambivalence” is a direct response to this essay. In “Visual Pleasure,” Mulvey investigates the textual strategies and the pleasures involved in classical cinema’s spectatorial engagement, laying out a societally and cinematically systemic dichotomy of sexual difference and concluding that in such classical cinema women have traditionally been represented as scopic objects of (male) pleasure, as passive bearers of male characters’ and spectators’ active desiring gaze. In Mulvey’s elucidation of what she calls the ‘masculinized’ spectatorship which emerges from such patriarchal structures, “masculinity as a ‘point of view’ is inscribed onto all spectatorial identification and pleasure in classical cinema (“Afterthoughts” 69). Like the many feminist scholars who attempted to rescue the female spectator from this oblivion and secure a more active, productive place for women both on and in front of the screen, Hansen in “Ambivalence” seeks to locate a space of “potential resistance to be reappropriated” for women within mainstream narrative cinema, an “alternative conception of visual pleasure” for the female spectator of mainstream Hollywood cinema (261). Additionally, Hansen also uses both Mulvey’s gendered structuring and the star figure of Rudolph Valentino to trace the emergence of that gendered, i.e. “structurally masculinized,” spectatorship in classical cinema, which she argues became institutionally and conventionally codified in the transition out of the silent era (Babel 5).

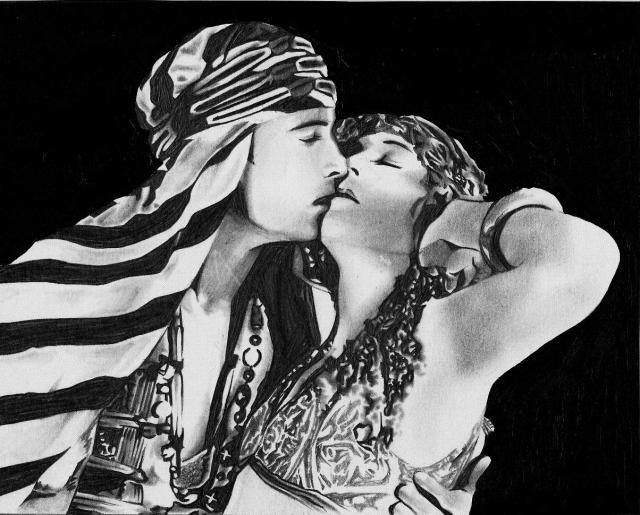

Because of this research focus, the main methodology of Hansen’s Valentino scholarship centers primarily on close textual analysis of his films’ viewing strategies and organizational systems and their impact on (female) spectators. She is thus able to examine pre-classical placements of the (female) spectator as well as the types of visual pleasure such engagements were capable of providing beyond the theories of masculinized spectatorship outlined by Mulvey and others, expanding and adding to accepted notions of the female spectator and to film history in general. And though Hansen does move beyond “the primacy of the film object” towards broader cultural considerations of “the cinema as an economic and social institution” in her follow-up, widely-researched book Babel and Babylon: Spectatorship and American Silent Film (1991), her main reading of the significance of the Valentino figure lies in the ambivalent spectatorial engagement his films offered women in the 1920s, a profitable ambivalence which she claims was also productively mirrored in his extratextual star image (Babel 5). In his “ambivalent” films, Hansen locates both the “alternative conception of visual pleasure” and the point of potential female resistance she sought: here, the Valentino characters oscillate between and embody both of the two viewing positions polarized in the dichotomy with which Mulvey characterized classical cinema, the active male controller of the gaze (and narrative) and exhibitor of the desirous look versus the passive female scopic object, the recipient of male voyeuristic and fetishistic looking (715-6).

This oscillation blurs Mulvey’s structure of sexual difference and opens up a space for female subjectivity in (patriarchically-dominated) mainstream cinema, specifically in this historical moment of early cinema, blooming modernity, and an emerging public sphere. Hansen writes that Valentino’s films productively offered female spectators a positive engagement beyond mere narcissistic identification with the passive female on screen or masochistic identification with the active male, as would later become the case with the solidification of classical cinema. By combining the “masculine control of the look with the feminine quality of ‘to-be-looked-at-ness,’” Valentino’s characters thereby created a space for the desiring female viewer and hence, importantly, female subjectivity in mainstream cinema (“Ambivalence” 263). Additionally, his ambiguous positioning, both within the diegesis of his films and extratextually in his star image, inherently argues for an ambivalence in spectatorial identification and textual structuring, and “urges us to insist upon the ambivalent constitution of scopic pleasure” in cinema (264).

Though Valentino’s films might initially resemble classic examples of Mulveyan textual strategies of sexual difference, with their narratives ultimately condemning the “vamp” women who gaze desiringly at Valentino and rewarding with heterosexual coupling the “good” girls who receive but don’t reciprocate Valentino’s look, Hansen argues that these films actually subvert such a reinforcement of patriarchal power by contradictingly positioning him, along with the women, in the “feminine” position of erotic object. Hansen writes that Valentino’s is “a gaze that fascinates precisely because it transcends the socially imposed subject/object hierarchy of sexual difference,” and because Valentino is not only the masculine looker but also, like the traditional “good” girl, looked at, is a scopic object of pleasure for the (female) spectator’s gaze; for women, she writes, the “erotic appeal of the Valentinian gaze… is one of reciprocity and ambivalence, rather than mastery and objectification” (“Ambivalence” 265). This ambivalent filmic position opens up an avenue within classically masculine structures of cinema and spectatorship for an alternative system of male-female relationships and power as well as for a reciprocal female desire which is usually denied (266).

After using textual analysis and psychoanalytic frameworks of textual viewing strategies to prove this subversive, positively ambivalent structuring of Valentino’s films, Hansen then uses similar means to reclaims two additional “alternative” aspects of visual pleasure for his female spectators: the pleasure of sadomasochistic rituals and the pleasure of recognition (264). This latter aspect of Valentino spectatorship rewards the (desiring) female spectator’s gaze both for recognizing the star onscreen and for successfully recognizing the Valentino figure, who often remained diegetically masked and disguised from the female characters in his many films which centered around narratives of costume, disguise, and deception. All of Hansen’s detailed, well-argued psychoanalytic explanations and analyses offer interesting and potentially useful readings of Valentino’s films and paint a very intriguing picture for the existence of alternative pleasures of female spectatorship before the masculinized structure of classic cinema had been fully cemented.

However, such primarily psychoanalytic scholarship ultimately seems rather limited and disappointingly a-historical after the hindsight of thirty years. Hansen attempts to remedy this in her wider-ranging book Babel and Babylon, where she explains that because “female identification within the dominant masculine structures is difficult, efforts to conceptualize a female viewer have gone beyond the psychoanalytic-semiotic framework to include culturally specific and historically variable aspects of reception” (5). Hansen makes an effort to adopt this broader type of strategy in Babel, where her scope has expanded to include the entire “public dimension of cinematic spectatorship,” yet with Valentino, her final case study in the book, she returns to these psychoanalytic conclusions and textual break-downs (7). Babel’s last chapter is an almost direct transcription of her 1986 “Ambivalence,” which effectively leaves such psychoanalytic explanations as her final word on Valentino, with lingering emphasis thus also given to her whole book on early spectatorship; this ultimately somewhat undercuts and diminishes the effectiveness of the extratextual, cultural work that she lays out as the project of the book and astutely explores elsewhere in it.

Regardless of such shortcomings, as well as an unfortunate overlooking of “the historical context of male film stardom,” Babel gave Hansen the extended space to more fully examine (female) spectatorship in relation to the public sphere, a topic which has marked most of the work of her career; she examines the ways in which “spectatorship is profoundly intertwined with the transformation of the public sphere, the gendered itineraries of everyday life” (Studlar “Babel” 40; Hansen Babel 2). Thus, Hansen traces the historical emergence and construction of film spectators not merely as textually-imagined, passive entities but as real participants in a heterogeneous social audience; by addressing the cinema as a social and commercial institution, she is able to identify the spectator as a consumer as well as an assumed figure of textual address. By extension, Hansen now also discerns female spectators as being constructed by desire, in relation to both film and star texts, both personal engagement and industrial production, which importantly nuances traditional conceptions of their fandom and filmic engagements and incorporates a larger awareness of the social and industrial structures at work around spectatorship. Within this broader, extra-textual scope, in Babel’s first chapter on Valentino, Hansen productively investigates the star not only within the textual structures of his films, but also in relation to the Hollywood star system of which he was a part, as Richard DeCordova had originally suggested in his 1986 “response” to “Ambivalence.” Thus Hansen complements her textual analysis with contextualizing cultural and historical research, locating Valentino as a visible “emblem of the simultaneous liberalization and commodification of sexuality that crucially defined the development of American consumer culture” at this time (2).

With such extratextual research, Hansen can also more fully explore the positive “ambivalences” of Valentino not only in relation to his films’ spectators but also to his fans, to the women of the “public sphere” of the culture in which he was a star; Hansen reads Valentino as “a figure and function of female spectatorship,” one who existed (or at least was seen to exist) to be looked at and desired by women and who existed because women looked at and desired him, both as an actor/character within his films’ diegesis and as a “real” man/star. This created an avenue for the expression of female desire not only in the relative privacy of the movie theater, which Hansen conceived of as a modern public space, but also in the public sphere at large. Hansen also extends the ambivalences of female desire itself to this public sphere, explaining that Valentino’s stardom exposed female spectatorship’s “precarious status as both cult of consumption and manifestation of an alternative public sphere,” as both potential victim of manipulation by Hollywood’s commercial construction of desire and empowering means of expressing female desire and subjectivity where women had been traditionally unable to do so (253). Thus, she writes, Rudolph Valentino “beckon[ed] with the promise of sexual – and ethnic-racial – mobility… appealed to those who most keenly felt the need, yet also the anxiety, of such mobility, who themselves were caught between the hopes fanned by the phantasmagoria of consumption and an awareness of the impossibility of realizing them within existing social and sexual structures” (268).

But despite these well-illustrated, detailed arguments about the creation of alternative pleasures and public spaces for women in this modern period of transition, and the usefulness of Valentino’s ambiguity in relation to their expression of desire and the possibilities of female spectatorship at this time, Hansen’s research and arguments have a few blind spots, which Studlar’s own critical focus allows her to address; male spectatorial response to Valentino and his ethnically-other background simply do not optimally fit into Hansen’s psychoanalytic models and her cultural research focus, and thus are less satisfactorily addressed in this scholarship. Hansen’s historical project lies primarily with female spectatorship (Valentino as “a figure and function of female spectatorship”), in contrast to Gaylyn Studlar’s focus on male spectatorship and discourses of masculinity in this period, and thus she concludes that “racial and ethnic stereotypes are inseparable from inscriptions of gender and sexuality, especially female sexuality” (255).

Female subjectivity, the main focus of Hansen’s scholarship and historical inquiry, ultimately ends up making her arguments, especially as it concerns Valentino in particular, appear largely one-sided, for she traces much of this modern period’s cultural and historical discourses back to women and to sexuality, to Freud and Lacan. For example, Hansen offers psychoanalytic analysis to explain Valentino’s ethnically-other yet clearly-desired identity in the sole terms of what she sees to be the fear and threat of female sexuality, which she links to the public emergence of the New Woman and a tradition of American fear and fascination with miscegenation. The complicated historical and cultural currents and discourses of this 20th century society of “blatant xenophobia” become reduced to a mere “displacement, a defense against the threat of female sexuality,” subordinated to the workings of the unconscious (255; Masquerade 4). As Studlar writes in her review of the book, it appears at times that “Hansen’s exploration of extratextual materials attached to Valentino’s stardom never seeks in a significant way to embrace a broader analysis of the cultural-historical moment” (40). Though Hansen compellingly locates the female spectator within the experience of cinema as it moved into modernity’s new public sphere, a Freudian coping mechanism, interesting and initially enlightening and more intriguing when applied to Valentino’s films themselves, unfortunately seems insufficient to wholly explain the huge cultural phenomenon that was the ambivalent figure of Rudolph Valentino, nor to explain factors like the racially-charged elements of culture as revealed in and exacerbated by Valentino’s stardom.

Gaylyn Studlar began her own Valentino scholarship with an initial response to Hansen’s “Ambivalence,” and in the process of development from this preliminary “response” (1987) to her final book This Mad Masquerade: Stardom and Masculinity in the Jazz Age (1993), she published her initial investigations into Valentino in “Discourses of Gender and Sexuality” (1989). In addition, Studlar also published a 1993 book review of Hansen’s Babel which, like her “Response” to the first essay, reveals her own specific research interests and the direction she would take with Valentino, outlining the differences of approach and inquiry between herself and Hansen in their joint exploration of the star figure Rudolph Valentino.

The title of her interim essay, “Discourses of Gender and Ethnicity,” like Hansen’s titles, reveals Studlar’s particular research focus and historic inquiry, which is culturally historic like Hansen’s but which centers around Jazz Age social discourses of gender (specifically masculinity) and ethnicity and the role of Hollywood stars rather than the specific positioning of 1920s (female) spectators and their emergence into a new public sphere. Though Studlar’s professional bibliography reveals overlapping interests in both male and female stars, spectatorial engagement, and filmic representations, her approach to Valentino eschews much of the textual structural analysis that defines Hansen’s discussion of Valentino’s films. Instead, she uses some textual narrative analysis to support her exploration of what are mostly the extra-textual elements of Valentino’s stardom and his star image, including publicity photos, newspaper and magazine interviews and articles, write-ins to the press from American men and women, and the gossipy facts and rumors which circulated about his ethnic identity, his background in dance, and his many and somewhat scandalous relationships with women. In her book’s introduction, Studlar explains that in contrast to some of her previous theoretically-oriented scholarship, this work on male stars is premised primarily upon her interest in American culture and “grounded in the specific cultural history of the period,” rather than exact theoretical definitions of terms like masquerade, for example. By looking towards these types of sources, in this moment when the star system was becoming a fully-fledged cultural phenomenon, Studlar is able to interrogate the various images of Valentino as they were constructed and perpetuated by the studios, by the press, by his films, by his “real life” biographical information, and even by himself on certain occasions, all for various commercial and professional motives and in complex interactions with the era’s social, cultural, and political discourses. Her “analysis focuses on the circulation of meaning created around a selected group of male stars” as well as on “how culture literally and figuratively ‘set the stage’ for that star” (Masquerade 3, 6). She also investigates male and female receptions of and reactions to that circulating star image, both textually and extra-textually, in order to more fully identify and engage with the dominant discourses of gender, ethnicity, and sexuality which were circulating in American society at this time of new modernity, of transition, of movement and change, and which became visible when voiced around the locus of Rudolph Valentino.

Studlar was clearly inspired by Hansen’s work on Valentino and appreciative of most of it; but where Hansen seems to be trying to explain culture through the figure of Valentino and his films (and psychoanalytic theory), Studlar appears more interested in the culture itself and the way it shapes and produces and becomes manifested in various forms, such as in Hollywood star figures. Studlar attempts to read Jazz Age American culture and its prevailing discourses of masculinity, ethnicity, and sexuality through the construction and reception of Valentino’s star image, using him as a gauge of popular cultural discourses and national preoccupations. Studlar finds a common link for her book’s four male star case studies in a unifying “paradigm of transformative masculinity” which was a product of the “the period’s extremely self-conscious negotiation of tradition and modernity, femininity and masculinity” and of its literary and cultural representations of gender as a performance, a process, a “mad masquerade” (4-5). \ Within this larger framework of then-circulating preoccupations with transformation and change, Studlar investigates Valentino specifically in relation to the cultural concept of “dance madness” which was sweeping the nation at the time, focalizing Valentino through that era’s view of dance as a case study for identifying the dominant cultural trends of the time. Noting the star’s dual positioning in relation to both the commercial film system and the realm of desiring/ identifying fans that Hansen too explored, Studlar explains that for Valentino, who had a background in dance and whose film career was characterized by his high degree of agile athleticism and a focus on his (dancer’s) body, dance was “the most important cultural influence on the meaning of the star profitably shaped by the industry discourse and pleasurably experienced by film spectators,” the most effective way of identifying the cultural currents which were already in circulation in the American society that made Valentino a star (7).

By extension, she also uses Jazz Age cultural discourses of masculinity, as embodied in Valentino’s star and filmic images and in the gendered public responses to him, to see “how American masculinity negotiated various social and sexual dilemmas of the time,” such as women’s increased sexual and economic freedom and the large influx of ethnically-other immigrants (5). Thus, she not only uses star figures to identify cultural concerns and then-dominant definitions of masculinity but also to ascertain the various responses that were employed by society at the time in response to its perceived threats and anxieties. So, in contrast to Hansen’s more theoretical, psychoanalytic formulations of such male and female responses to Valentino and the cultural and historic changes of the time, Studlar grounds her similar investigations in the figure of Valentino himself, in the definitions of masculinity he embodied, and the cultural discourses mobilized around him, as well as in the specific culture itself.

Studlar’s well-organized, deeply-researched, highly-engaging scholarship has the interesting benefit of registering the perceived concerns and responses of the time in a reception history that reveals a portrait of the time beyond mere historical “facts;” to a large extent, perceived reality is reality for the people living it, and by using the figure of Valentino to register prevailing social perceptions, Studlar is able to record the social realties which overlay concrete historical and cultural fact. Thus Studlar shows the complex ways in which Valentino figured prominently and importantly within the “perceived crisis in American sexual and gender relations” of the time, how he, “like dance, had become symbolic of tumultuous changes believed to be taking place in the system governing American sexual relations” (196-7). Furthermore, Valentino and his star text, and the sexually ambiguous, “dance mad” masculinity he represented, seemed to confirm the “increasing effeminacy of men and the masculinity of women” which was perceived by the culture (mostly its men) of this time (186).

In exploring the relationship between stars, the star phenomenon in general, and culture, Studlar is able to examine “the circulation of meaning around masculinity as a cultural concept” by way of these four male stars (4). For instance, as both Hansen and Studlar address, Valentino’s past career as a dancer tied into his feminized persona of being “a creation of, for and by women,” as Hansen wrote, a popular conception created by his immense dependence on the desire and adoration of female fans to remain a Hollywood actor and star, his being “discovered” by June Mathis, screenwriter of his star-making film Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse, as well as his well-publicized relationships with dominating, sexually-vampish and –ambiguous women like dancer Natacha Rambova, whose platinum “slave bracelet” he wore (“Ambivalence” 262, 261).

However, whereas Hansen saw such popular characterizations and perceptions of Valentino as linked to negative ideas of his being dependent upon women and to the new liberalized female sexuality and identified them as a largely male defense against the threat he posed in terms of female sexuality, Studlar uses these same circulating star images and perceptions to identify larger cultural anxieties and discourses beyond female sexuality. Studlar explains and explores Valentino’s pre-film career as what was derogatively called a “lounge lizard” or “tango pirate,” men paid by women to be their dance partners and to teach them the latest steps, and the public male-voiced outcry against it. She reads this negative male response in relation to the threatening new expressions of liberalized female sexuality and the (male) perception of women’s “actively searching for pleasures” which such “lounge lizards” made all too visible and which they easily facilitated in the newly expanding public sphere (159). But such responses also relate to (and help Studlar identify) not only perceived threats, but also the traditional, dominant American masculinity they appeared to be displacing. Epitomized by the Rooseveltian cult of virility, these more traditional codes of masculinity were perceived to be under particular threat as Valentino’s and the lounge lizards’ more ambiguous, feminized, “dance mad,” and often racially-other type of masculinity were embraced by women, both by film fans and by the many women going to dance halls and jazz clubs in the 1920s. By examining all of these elements in relation to each other, Studlar moves beyond the limiting realm of female sexuality to get at the ambiguous and complex web of discourses, social transformations, and cultural threats which were circulating in American culture at this historical moment.

Additionally, Studlar’s research satisfyingly engages with the highly problematic ethnic aspect of Valentino’s stardom, linking such negative outcry against what was characterized as his effeminate, non-American image to the xenophobia which was prevalent at this time; she connects these rampant expressions of xenophobia to the newly Eastern and Southern European, versus the previously Western European, demographic of immigration, the nativist movement which had been building since the 1890s, and ensuing ideas of racial purity and eugenics. Additionally, such racial discourses further compounded the threat and anxiety caused by Valentino’s characterization as a “tango pirate” type of man, both in his past career and in his films which frequently played on this own biography and on his lean, athletic body by incorporating dance into the narrative, for Studlar writes that the “darkly foreign” immigrant was the most dangerous incarnation of the already-existent stereotype of “sexualized and greedy masculinity” epitomized by “lounge lizards,” or “boy flappers” (151). Thus Studlar acknowledges multiple cultural perceptions and discourses which were broadly circulating during the American Jazz Age, which become succinctly visible as responses to the so-called feminized masculinity and the dancer and racially-other characteristics of Valentino’s star texts.

In returning to her unifying theme of this modernity’s “transformative masculinity,” Studlar further explains that Valentino became especially troubling to Jazz Age America(-n men) (and full of positive potential for its women) because he (and his films) revealed a transformation of masculinity, or rather subverted then-dominant patterns of transformation, as opposed to the “oscillation between sadistic and masochistic” positions outlined in Hansen’s “ambivalence”-stressing scholarship. Such structures and narratives of transformation well matched organizations of the popular-among-women romance novel as analyzed by scholar Janice Radway, potentially explaining his films’ appeal among women, as well as this modern era’s “obsession with the transformative potential of masculinity” (171). These narratives of transformation, which defined popular Harlequin romances, for example, characterized some of Valentino’s early star-making vehicles, such as Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse wherein he narratively progressed from “male butterfly to sacrificing war hero” (175).

However, such transformations do not characterize most of his films. Rather, as Studlar writes in her cultural history, Valentino’s racially-other, sexually ambiguous, feminized masculinity ultimately “could not be transformed into traditional American masculinity,” either through such conventional and popular narrative patterns or in his own star image (176). Whereas most ethnic stars like Tony Moreno had been assimilated into normative ethnic and masculine codes, Valentino’s films, with their emphasis on dance, physical disguise and transformation, and the (male) dancer’s body, suggested an ambiguous “nuanced range of erotically charged moods” in contrast to the dominant patriarchal notion of controlling masculinity and also productively “visually redefined the cinematic images of the male body” at this time (191). Therefore, as Studlar concludes, Valentino ultimately presented the intensely troubling (to men) and massively desired (by women) figure that he did to Jazz Age America because, narratively and extratextually, his “vehicle for masculine transformation” did not assimilate him to dominant discourses of gender and ethnicity but instead left him “culturally poised between a traditional order of masculinity and a utopian feminine ideal” (197). The star figure of Valentino converged “female fantasy with the dangerous, transformative possibilities of dance and with the highly restrictive norm for constructing ethnic masculinity in a frankly xenophobic nation,” creating both a site of tension and potential resistance, leaving him to embody “anxieties for some…promise to others” (197).

Forgoing any grand, all-encompassing, theoretical conclusions, choosing instead to embrace the ambiguities and contradictions and overlaps of her cultural research through the star figure of Rudolph Valentino, Studlar concludes by explaining that Valentino presented not a unique case, but “a higher order of problematic” for a culture already struggling with the issues brought up and exacerbated by his stardom and his star texts (197). Thus does she avoid the “dehistoricizing theoretical orthodoxy” that threatened Hansen’s scholarship, offering a new type of historical inquiry which merges disciplines of study and eschews Grand Theories to paint a picture of society as it was seen by those living within and making it (Studlar “Babel” 40).

Bibliography

deCordova, Richard. “Richard deCordova Responds to Miriam Hansen’s ‘Pleasure, Ambivalence, Identification : Valentino and Female Spectatorship’ (“Cinema Journal,” Summer 1986).” Cinema journal 26.3 (1987): 55-7.

Erens, Patricia. Issues in Feminist Film Criticism. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1990.

Hansen, Miriam. Babel and Babylon: Spectatorship in American Silent Film. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1991.

—. “Pleasure, Ambivalence, Identification: Valentino and Female Spectatorship.” In Stardom: Industry of Desire. Ed. Christine Gledhill. London: Routledge, 1991. Originally published in Cinema Journal 25.4 (1986): 6-32.

“Many Hurt in Mad Fight to Pass Valentino Bier.” Boston Daily Globe. ProQuest Historical Newspapers. Aug 25 1926.

Mulvey, Laura. “Afterthoughts on ‘Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema’ inspired by Duel in the Sun.” In Feminism and Film Theory. Ed. Constance Penley. New York: Routledge, 1988. 69-79. Originally published in Framework 15/16/17 (1981): 12-15.

—. “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema.” In Film Theory and Criticism. Ed. Braudy, Leo and Marshall Cohen. 7th ed. New York: Oxford University Press, 2009. 711-22.

Studlar, Gaylyn. “Discourses of Gender and Ethnicity.” Film Criticism XIII.2 (1989): 18-35.

–. “Gaylyn Studlar Responds to Miriam Hansen’s “Pleasure, Ambivalence, Identification: Valentino and Female Spectatorship” (“Cinema Journal,” Summer 1986).” Cinema Journal 26.2 (1987): 51-3.

–. Rev. of Babel and Babylon: Spectatorship in American Silent Film, by Miriam Hansen. Film Quarterly 47.1 (1993): 39-40.

–. This Mad Masquerade: Stardom and Masculinity in the Jazz Age. New York: Columbia University Press, 1996. 150-98.

“Thousands in Riot at Valentino Bier; More than 100 Hurt.” New York Times. ProQuest Historical Newspapers. Aug 25, 1926.

“Valentino Passes with No Kin at Side; Throngs in Street.” New York Times. ProQuest Historical Newspapers. Aug 24, 192.